Claire Cameron

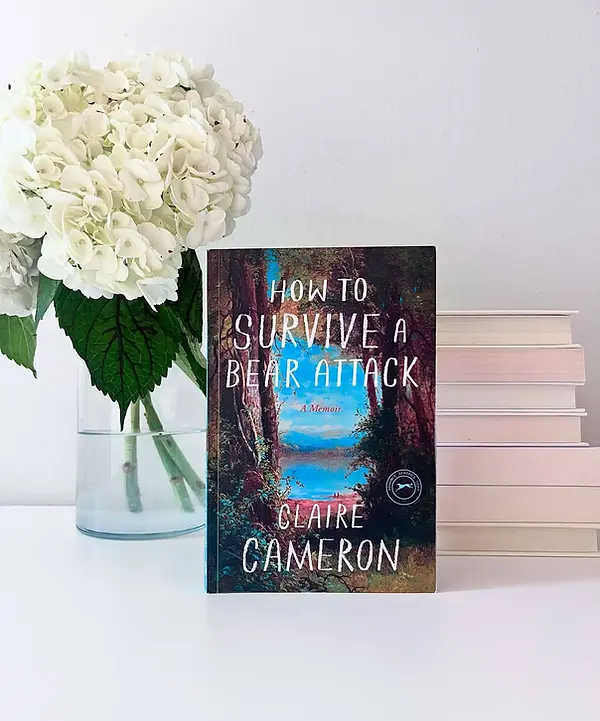

Author of HOW TO SURVIVE

A BEAR ATTACK

On a cool October evening in 1991, a couple arrived to a small, remote island in Algonquin Park and never left. For years, the events surrounding their demise consumed Claire Cameron’s waking and dreaming mind.

A memoir that poignantly blends genres, becoming part investigation, part study, How to Survive a Bear Attack is an absorbing portrait of grace under fire. Piecing together the last hours of a Toronto couple and the black bear that attacked them, Cameron invites readers on an intimate journey, detailing her own encounters with the unexpected as she receives a cancer diagnosis that will drastically alter her relationship with the outdoors.

“The best stories may be old, but they are never static. They change and adapt to fit the context they are told in. A story can't change what happened in the past, but it can offer comfort, guidance, or solace to those who are still alive. Through this story, I found my voice again.”

Image: Trish Mennell

Gripping and immersive, expertly researched and wholly alive, How to Survive a Bear Attack explores what it means to be human (and animal) in circumstances beyond our control, while facing unanticipated scenarios in wildernesses both internal and external.

Girls on the Page

When did you first realize that you wanted to become a writer, and what did that discovery feel like?

Claire Cameron

In my 20s, I read all the time, but I was too twitchy to sit down and write. When I wasn’t working, I was hiking, paddling, and climbing mountains. When I turned 30, I had the impulse to make something. I started working on an album. I can sing and play the guitar, but I’m not great. For some reason, I was determined to write and record all the songs myself. I started writing songs and learning the bass. I spent months recording the parts and editing all the tracks. By the end, I had an album. I used to sing in a choir, so the vocals had that kind of vibe. But I was into Motörhead at the time, so mixing those two elements was a bold choice. I’m not being modest when I say – my album wasn’t great. But I did like the lyrics I wrote. One of the songs was called Painting Lines. It was about a guy who had a job putting lines on the highway. I liked how the song traced his arc. It occurred to me that I knew so much about him, almost like there was a novel behind the story. Then I realized I’m much better at typing than playing the guitar. That’s how my first novel, The Line Painter, came to be.

The black bear has been a recurring motif in your work, from your 2014 novel, The Bear, which was inspired by the incident on Bates Island, to How to Survive a Bear Attack, a book that presents as part memoir, part investigation and part study. In it, you write:

“I’ve come to understand that behind my obsession with this specific incident lay a question: If I’m attacked by a bear, will I survive? At its heart, this book tells the story of how I found the answer.”

Can you share more about the decision to format the book this way, interlacing the attack with your own narrative, along with those from the search party, as well as including the perspective of the black bear?

This book started as a straightforward investigation. I had heard so many things about the bear attack on Bates Island in Algonquin Park. A black bear killed two people. I knew it had happened, but so many of the details I heard about the attack sounded more like a horror film than reality.

My novel, The Bear, came from those. I started writing How to Survive a Bear Attack because the attack was still haunting me. If I found out the truth of what happened, maybe I could set my fears aside? The first draft of the book laid out the facts — it told the story of what happened that night when a bear attacked in 1991. There was a problem with that draft. I love bears. I had studied them for years. And I had just written a book where, at the end, a big bad bear came and attacked. There are so many books like that, I didn’t think the world needed one more. I put the manuscript aside. The breakthrough came when I went beyond that question. Not just what happened, but it was when I started to ask why it happened. I started the nature writing element and explored the story from the bear’s perspective. And then, finally, why had I been obsessed with this story for so long? Answering that question required a layer of my story. The book became part-memoir.

A striking cinematography guides readers through Ray and Carola’s story: from driving north to Algonquin Park that weekend in October with your descriptions of the Canadian Shield, to the couple’s last moments on the island.

Early in the book you write: “The past hovers in the distance, prone to blurring. Some accounts are unreliable, many witnesses are lost, all versions of a story become intangible. An investigation is an attempt to do the impossible, to reach out and touch and describe how it felt, the taste, the smell. But the past is a land we can’t visit anymore. I can’t bring it back, but I can try to tell a complete story. It’s a way of passing on the feeling of standing somewhere we can no longer be.”

I’m curious to hear more about what it was like writing through a stylistic lens while balancing the responsibility of presenting the facts and details of your research, as well as the weight of knowing that the couple’s respective families might eventually read the book.

I used different genres to write this book. I switch between an investigative approach, memoir, and there is also speculative fiction. All of these tools are valid ways of trying to find different kinds of truth. In putting them together, I felt it was important to be clear about my sources. I included notes in the back. In the text, I tried to be clear about where I was drawing from.

The big difference between writing this book and my novels was my responsibility to various parties, including victims, their friends and family, the first responders, scientists whose work I was representing, the characters I met along the way, my family, and the bear. While I was writing, I was conscious of them. This is a book about healing and recovery. I tried to stay true to that.

The geographical and situational details in this book are breathtaking—for example, a large portion of the book is written from the perspective of the black bear as he travels through seasons, looking for food, trying to survive. As a writer, do you find that you’re constantly observing the world around you and collecting material, or are you able to “turn off’ the authorial muscle in your brain?

I don’t have a brain that turns off. I am either wide awake or sound asleep. I don’t have a gear that I can shift in between those two things. This means I am much happier when I am working on a book. Everything I see or do becomes part of my observations for whatever I’m writing. Also, if my mind wants to cast backward, then my memories can serve my work, too. It means I’m never bored. I can be standing in line at the grocery store and thinking about how humans are scavenging in the aisle, or how consumerism co-opts our instincts to gather food. Even if I’m not at my computer, my mind is often working on my writing.

Throughout the novel, descriptions of nature bring the story alive in such a vivid way.

You describe the bleeding horizon of an Algonquin Park sunset, the elegant, regal white pines which possess something wise inside. I’d love to hear more about how nature informs your writing.

I’m not sure nature informs my writing as much as it informs how I see the world. Everything is connected. I don’t believe that anything is artificial or unnatural. If humans made something, it’s because we combined elements that we found on earth. I see humans as animals. The difference between us might be that we don’t live in a sustainable way, whereas most animals do. I don’t think we are superior to other living things. That includes a tree, a river, or a bear.

There’s a scene where you describe having a glass of wine in a bar following a profound personal discovery: “The wine reminded me of what I’d been missing. There are small pleasures that bring warmth and light to the skin. I let myself feel them. When the picture is too overwhelming, it can help to appreciate life on a smaller scale.”

What small-scale pleasures do you find yourself gravitating toward while working on a writing project—or even just as recesses to the weight of everyday life?

Smaller pleasures, I have to remind myself to enjoy them. Writing a novel requires a sustained effort. I have a fairly rigid route that helps me catch a mindset.

But I can get caught in the larger project and can forget to enjoy myself. I run this way too. I don’t go for little jogs, it has to be a long, hard run for some reason.

So, I make sure there are good things in my routine, hot baths, soft pyjamas, good books, great music. I’m not a great cook, too impatient, but my husband takes the time to make amazing spreads. I swear it’s the secret of our relationship. I will never, ever leave him.

Do you have an ideal set-up, place, or time of day to write?

Oh yes! Morning. Always morning. The earlier, the better. It’s best if I go straight to the computer with my first cup of coffee. I have two cats, two boys, a dog and a husband, so this isn’t always realistic. I work at a desk top with a large monitor. I wear industrial ear muffs that are rated to 28 decibels. I like to have a door I can shut—and if it has a lock, that’s better. I need to be able to sink into a deep level of concretion. It feels more like acting when I’m writing well, it’s like I’m in a flow.

“Time, people, love, they are fleeting. We are born, grow, and move across the land until we pass by. The world is in a constant state of change. My life is no exception even if, sometimes, or for a brief moment, I may have tricked myself into thinking otherwise.”

—Claire Cameron, from How to Survive A Bear Attack

You have a wonderful Substack called Books I Love, where you highlight your favorite reads. Books are made from other books, you write there. Can you curate a list of five books—whether similar in subject matter or tone—that readers will enjoy after finishing How to Survive a Bear Attack?

I recommend books I love. My Substack is that simple. The last novel I recommended was

Jaws by Peter Benchley. It’s dated in many ways and that, I think, makes it a perfect nostalgic summer read – the book is better than the movie.

Then, because How to Survive a Bear Attack has elements of mystery, nature writing, and memoir, the list is eclectic:

I am, I am, I am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell – This is one of my favourite memoirs. It does exactly what it says, but then she lands the concept in a way that continues to astonish me. I’m not going to give it away.

Touching the Void by Joe Simpson – It’s a first person account of a self-rescue after a mountaineering accident. It’s a classic for a reason. Reading it is like experiencing a brush with near-death. Once you are done, you feel completely alive.

The Knowing by Tanya Talaga – In my book, I only start to touch the colonial myths of wilderness, identity, and our relationship with the land. I have learned so much from indigenous authors, this book is one example. It tells the story of our country that I didn’t learn at school. It’s incredible. I’ve read it twice and I’ll read it again.

In the Eye of the Wild by Nastassja Martin – This is a translation, a French anthropologist tells the story of when she was attacked by a bear in Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. She details her physical and mental transformation after that attack – and how she came to make peace with it.

What surprised you most, whether about the subject matter or yourself, while researching and writing this book?

Everything about this book surprised me. Starting out, I didn’t understand why, after I was diagnosed with cancer, I became obsessed with this bear attack. I didn’t think cancer and a bear attack were related. I could have never guessed how one would give me such insight into the other.

Bears are such feared, misunderstood creatures, yet you do a wonderful job of educating the reader and bringing them into the mind of the animal.

To survive as a wild bear means engaging in a constant calculus.

There is much to learn from this book: for example, how bears have a reflective layer—“tapetum lucid”—in their eyes. That they can detect humans from up to twenty miles away. How the oldest known black bear lived to be thirty nine and a half years old. What do you hope readers learn or take away from black bears after reading?

I hope they see black bears as individuals. Each bear is different. They have personalities. They make decisions. There is as much variation between each bear as there is between each person. Understanding this is, I think, the foundation for building our respect for bears. We have a lot in common with them. They are incredible animals. We need to learn to better co-exist with them.

There’s so much beauty in a constant state of discovery, you write towards the end of

How to Survive a Bear Attack.

What’s a recent discovery that has brought you joy?

As I write in my book, I have to limit UV exposure. It means I live a smaller life in the summer. A lot of my joys are found between the covers of a book. I just finished an advance copy of a book by Trina Moyles called Black Bear. It will be out in January, but I absolutely loved it. She tells the story of her relationship with her brother and how she came to co-exist with an extended family of bears. Also, I was lucky enough to read Miriam Toews' new one, A Truce that is Not Peace, out in September. It’s a memoir and every bit as charming, engaging, and thoughtful as her novels.

Claire Cameron's novels include The Bear and The Last Neanderthal. Her recent memoir, How to Survive a Bear Attack, is a national bestseller. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Guardian, and she is a monthly contributor to The Globe and Mail. She lives in Toronto.

To buy a copy of How to Survive a Bear Attack, consider supporting one of Claire’s favorite bookstores: Type Books, Flying Books, McNally Robinson, Cedar Canoe Books, and Librarie Drawn & Quarterly.

Interview by Emma Leokadia Walkiewicz

© Girls on the Page 2026